Tanzania

United Republic of Tanzania Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania (Swahili) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Uhuru na Umoja" "Freedom and Unity" | |

| Anthem: "Mungu ibariki Afrika" "God bless Africa"[1] | |

| |

| Capital | Dodoma 6°10′S 35°44′E / 6.167°S 35.733°E |

| Largest city | Dar es Salaam 06°48′S 39°16′E / 6.800°S 39.267°E |

| Official languages | |

| Other languages | Over 100 languages, including (1m+): |

| Religion (2020)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Tanzanian |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential republic |

| Samia Suluhu Hassan | |

| Philip Mpango | |

| Kassim Majaliwa | |

• Speaker | Tulia Ackson |

| Ibrahim Hamis Juma | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 9 December 1961 | |

• Zanzibar | 10 December 1963 |

• Unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar | 26 April 1964 |

• Current constitution | 25 April 1977 |

| Area | |

• Total | 947,303 km2 (365,756 sq mi) (30th) |

• Water (%) | 6.4[5] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 67,462,121[6] (23rd) |

• 2022 census | |

• Density | 65.2/km2 (168.9/sq mi) (147th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2017) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | low (167th) |

| Currency | Tanzanian shilling (TZS) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (East Africa Time) |

| Calling code | +255[b] |

| ISO 3166 code | TZ |

| Internet TLD | .tz |

Tanzania,[c] officially the United Republic of Tanzania,[d] is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to the south; Zambia to the southwest; and Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west. According to the 2022 national census, Tanzania has a population of around 62 million, making it the most populous country located entirely south of the equator.

Many important hominid fossils have been found in Tanzania. In the Stone and Bronze Age, prehistoric migrations into Tanzania included Southern Cushitic speakers similar to modern day Iraqw people who moved south from present-day Ethiopia;[13] Eastern Cushitic people who moved into Tanzania from north of Lake Turkana about 2,000 and 4,000 years ago;[13] and the Southern Nilotes, including the Datoog, who originated from the present-day South Sudan–Ethiopia border region between 2,900 and 2,400 years ago.[13]: page 18 These movements took place at about the same time as the settlement of the Mashariki Bantu from West Africa in the Lake Victoria and Lake Tanganyika areas.[13][14] In the late 19th century, the mainland came under German rule as German East Africa, and this was followed by British rule after World War I when it was governed as Tanganyika, with the Zanzibar Archipelago remaining a separate colonial jurisdiction. Following their respective independence in 1961 and 1963, the two entities merged in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania.[15] Tanganyika joined the British Commonwealth and Tanzania remains a member of the Commonwealth as a unified republic.[16]

Today, the country is a presidential constitutional republic with the federal capital located in Government City (Dodoma);[17] the former capital, Dar es Salaam, retains most government offices and is the country's largest city, principal port, and leading commercial centre.[15][18][19] Tanzania is a de facto one-party state with the democratic socialist Chama Cha Mapinduzi party in power.[20] The country has not experienced major internal strife since independence and is seen as one of the safest and most politically stable on the continent.[21] Tanzania's population comprises about 120 ethnic,[22] linguistic, and religious groups. Christianity is the largest religion in Tanzania, with substantial Muslim and Animist minorities.[23] Over 100 languages are spoken in Tanzania, making it the most linguistically diverse country in East Africa;[24] the country does not have a de jure official language,[2][3] although the national language is Swahili.[25] English is used in foreign trade, in diplomacy, in higher courts, and as a medium of instruction in secondary and higher education,[24][26] while Arabic is spoken in Zanzibar.

Tanzania is mountainous and densely forested in the north-east, where Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest mountain in Africa and the highest single free-standing mountain above sea level in the world, is located. Three of the African Great Lakes are partly within Tanzania. To the north and west lie Lake Victoria, Africa's largest lake, and Lake Tanganyika, the continent's deepest lake, known for its unique species of fish. To the south lies Lake Malawi. The eastern shore is hot and humid, with the Zanzibar Archipelago just offshore. The Menai Bay Conservation Area is Zanzibar's largest marine protected area. The Kalambo Falls, located on the Kalambo River at the Zambian border, is the second-highest uninterrupted waterfall in Africa.[27] Tanzania is one of the most visited tourist destinations for safaris.[28]

Etymology

The name Tanzania was created as a clipped compound of the names of the two states that unified to create the country: Tanganyika and Zanzibar.[29] It consists of the first three letters of the names of the two states ("Tan" and "Zan") and the suffix "-ia."

The name Tanganyika is derived from the Swahili words tanga "sail" and nyika "uninhabited plain, wilderness", creating the phrase "sail in the wilderness". It is sometimes understood as a reference to Lake Tanganyika.[30]

The name of Zanzibar derives from Zanj, the name of a local people (said to mean "black"), and Arabic barr "coast" or "shore."[31]

History

Ancient

Tanzania is one of the oldest continuously inhabited areas on Earth. Traces of fossil remains of humans and hominids date back to the Quaternary era. The Olduvai Gorge, in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, features a collection with remnants of tools that document the development and use of transitional technology.

The indigenous populations of eastern Africa are thought to be the linguistically isolated Hadza and Sandawe hunter-gatherers of Tanzania.[13]: page 17

The first wave of migration was by Southern Cushitic speakers who moved south from Ethiopia and Somalia into Tanzania. They are ancestral to the Iraqw, Gorowa, and Burunge.[13]: page 17 Based on linguistic evidence, there may also have been two movements into Tanzania of Eastern Cushitic people at about 4,000 and 2,000 years ago, originating from north of Lake Turkana.[13]: pages 17–18

Archaeological evidence supports the conclusion that Southern Nilotes, including the Datoog, moved south from the present-day South Sudan / Ethiopia border region into central northern Tanzania between 2,900 and 2,400 years ago.[13]: page 18

These movements took place at approximately the same time as the settlement of the iron-making Mashariki (Eastern) Bantu from West Africa in the Lake Victoria and Lake Tanganyika areas, as part of the centuries-long Bantu expansion. The Bantu peoples brought with them the west African planting tradition and the primary staple of yams. They subsequently migrated out of these regions across the rest of Tanzania between 2,300 and 1,700 years ago.[13][14]

Eastern Nilotic peoples, including the Maasai, represent a more recent migration from present-day South Sudan within the past 500 to 1,500 years.[13][32]

The people of Tanzania have been associated with the production of iron and steel. The Pare people were the main producers of sought-after iron for peoples who occupied the mountain regions of north-eastern Tanzania.[33] The Haya people on the western shores of Lake Victoria invented a type of high-heat blast furnace, which allowed them to forge carbon steel at temperatures exceeding 1,820 °C (3,310 °F) more than 1,500 years ago.[34]

Travelers and merchants from the Persian Gulf and India have visited the east African coast since early in the first millennium AD.[35] Islam was practiced by some on the Swahili Coast as early as the eighth or ninth century AD.[36]

Medieval

Bantu-speakers built farming and trade villages along the Tanzanian coast from the outset of the first millennium. Archaeological finds at Fukuchani, on the north-west coast of Zanzibar, indicate a settled agricultural and fishing community from the 6th century CE at the latest. The considerable amount of daub found indicates timber buildings, and shell beads, bead grinders, and iron slag have been found at the site. There is evidence for limited engagement in long-distance trade: a small amount of imported pottery has been found, less than 1% of total pottery finds, mostly from the Gulf and dated to the 5th to 8th century. The similarity to contemporary sites such as Mkokotoni and Dar es Salaam indicate a unified group of communities that developed into the first centre of coastal maritime culture. The coastal towns appear to have been engaged in Indian Ocean and inland African trade at this early period. Trade rapidly increased in importance and quantity beginning in the mid-8th century and by the close of the 10th century Zanzibar was one of the central Swahili trading towns.[37]

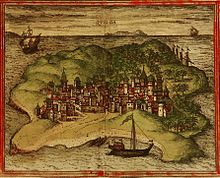

Growth in Egyptian and Persian shipping from the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf revitalised Indian Ocean trade, particularly after the Fatimid Caliphate relocated to Fustat (Cairo). Swahili agriculturalists built increasingly dense settlements to tap into trade, these forming the earliest Swahili city-states. The Venda-Shona Kingdoms of Mapungubwe and Zimbabwe in South Africa and Zimbabwe, respectively, became a major producer of gold around this same period. Economic, social, and religious power was increasingly vested in Kilwa, Tanzania's major medieval city-state. Kilwa controlled a number of smaller ports stretching down to modern-day Mozambique. Sofala became the major gold emporium and Kilwa grew rich off the trade, lying at the southern end of the Indian Ocean Monsoons. Kilwa's major rivals lay to the north, in modern-day Kenya, namely Mombasa and Malindi. Kilwa remained the major power in East Africa until the arrival of the Portuguese at the end of the 15th century.[38]

Colonial

Claiming the coastal strip, Omani Sultan Said bin Sultan moved his capital to Zanzibar City in 1840. During this time, Zanzibar became the centre for the east African slave trade.[39] Between 65 and 90 per cent of the Swahili population of Zanzibar was enslaved.[40][clarification needed] One of the most infamous slave traders on the East African coast was Tippu Tip, who was the grandson of an enslaved African. The Nyamwezi slave traders operated under the leadership of Msiri and Mirambo.[41] According to Timothy Insoll, "Figures record the exporting of 718,000 slaves from the Swahili coast during the 19th century, and the retention of 769,000 on the coast."[42] In the 1890s, slavery was abolished.[43]

In 1863, the Holy Ghost Mission established an early reception center and depot at Zanzibar. In 1877, responding to appeals of Henry Stanley following his trans-Africa expedition, and permission being given to Stanley by King Mutessa I of Buganda, the Church Missionary Society sent missionaries Edward Baxter and Henry Cole to establish inland missions.[44][45][46] In 1885, Germany conquered the regions that are now Tanzania (minus Zanzibar) and incorporated them into German East Africa (GEA).[47] The Supreme Council of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference awarded all of GEA to Britain on 7 May 1919, over the strenuous objections of Belgium.[48]: 240 The British colonial secretary, Alfred Milner, and Belgium's minister plenipotentiary to the conference, Pierre Orts, then negotiated the Anglo-Belgian agreement of 30 May 1919[49]: 618–9 where Britain ceded the north-western GEA provinces of Ruanda and Urundi to Belgium.[48]: 246 The conference's Commission on Mandates ratified this agreement on 16 July 1919.[48]: 246–7 The Supreme Council accepted the agreement on 7 August 1919.[49]: 612–3 On 12 July 1919, the Commission on Mandates agreed that the small Kionga Triangle south of the Rovuma River would be given to Portuguese Mozambique,[48]: 243 with it eventually becoming part of independent Mozambique. The commission reasoned that Germany had virtually forced Portugal to cede the triangle in 1894.[48]: 243 The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919, although the treaty did not take effect until 10 January 1920. On that date, the GEA was transferred officially to Britain, Belgium, and Portugal. Also on that date, "Tanganyika" became the name of the British territory. In the mid-1920s, the British implemented a system of indirect rule in Tanzania.[50]

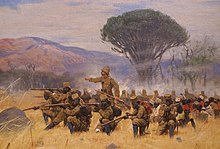

The Maji Maji Rebellion, between 1905 and 1907, was an uprising of several African tribes in German East Africa against the colonial authorities, in particular because of forced labour and deportation of certain tribes. It was the subject of a bloody repression, which combined with famine caused 300,000 deaths among the population, out of a Tanganyikan population of about four million.[51]

During World War II, about 100,000 people from Tanganyika joined the Allied forces[52] and were among the 375,000 Africans who fought with those forces.[53] Tanganyikans fought in units of the King's African Rifles during the East African Campaign in Somalia and Abyssinia against the Italians, in Madagascar against the Vichy French during the Madagascar Campaign, and in Burma against the Japanese during the Burma Campaign.[53] Tanganyika was an important source of food during this war, and its export income increased greatly compared to the pre-war years of the Great Depression.[52] Wartime demand, however, caused increased commodity prices and massive inflation within the colony.[54]

In 1954, Julius Nyerere transformed an organisation into the politically oriented Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). TANU's main objective was to achieve national sovereignty for Tanganyika. A campaign to register new members was launched, and within a year, TANU had become the leading political organisation in the country. Nyerere became Minister of British-administered Tanganyika in 1960 and continued as prime minister when Tanganyika became independent in 1961.[55]

Modern

British rule came to an end on 9 December 1961. Elizabeth II, who had acceded to the British throne in 1952, continued to reign through the first year of Tanganyika's independence, but now distinctly as Queen of Tanganyika, represented by the governor general.[56]: page 6 Tanganyika also joined the British Commonwealth in 1961.[16] On 9 December 1962, Tanganyika became a democratic republic under an executive president.[56]: page 6

After the Zanzibar Revolution overthrew the Arab dynasty in neighbouring Zanzibar, accompanied with the slaughter of thousands of Arab Zanzibaris,[57] which had become independent in 1963, the archipelago merged with mainland Tanganyika on 26 April 1964.[58] The new country was then named the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar.[59][60] On 29 October of the same year, the country was renamed the United Republic of Tanzania ("Tan" comes from Tanganyika and "Zan" from Zanzibar).[15] The union of the two hitherto separate regions was controversial among many Zanzibaris (even those sympathetic to the revolution) but was accepted by both the Nyerere government and the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar owing to shared political values and goals.[61]

Following Tanganyika's independence and unification with Zanzibar leading to the state of Tanzania, President Nyerere emphasised a need to construct a national identity for the citizens of the new country. To achieve this, Nyerere provided what is regarded as one of the most successful cases of ethnic repression and identity transformation in Africa.[62] With more than 130 languages spoken within its territory, Tanzania is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in Africa. Despite this obstacle, ethnic divisions remained rare in Tanzania when compared to the rest of the continent, notably its immediate neighbour, Kenya. Furthermore, since its independence, Tanzania has displayed more political stability than most African countries, particularly due to Nyerere's ethnic repression methods.[63]

In 1967, Nyerere's first presidency took a turn to the left after the Arusha Declaration, which codified a commitment to socialism as well as Pan-Africanism. After the declaration, banks and many large industries were nationalised.

Tanzania was also aligned with China, which from 1970 to 1975 financed and helped build the 1,860-kilometre-long (1,160 mi) TAZARA Railway from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to Kapiri-Mposhi, Zambia.[64] Nonetheless, from the late 1970s, Tanzania's economy took a turn for the worse, in the context of an international economic crisis affecting both developed and developing economies.

In 1978, the neighbouring Uganda, under the leadership of Idi Amin, invaded Tanzania. This disastrous invasion would culminate in Tanzania invading Uganda with the aid of Ugandan rebels and deposing Idi Amin as a result. However, the war severely damaged Tanzania's economy.[citation needed]

Through the 1980s, conservation oriented national parks such as Serengeti and Kilimanjaro, with Mount Kilimanjaro as the tallest freestanding summit on Earth, were included on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

From the mid-1980s, the regime financed itself by borrowing from the International Monetary Fund and underwent some reforms. Since then, Tanzania's gross domestic product per capita has grown and poverty has been reduced, according to a report by the World Bank.[65]

In 1992, the Constitution of Tanzania was amended to allow multiple political parties.[66] In Tanzania's first multi-party elections, held in 1995, the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi won 186 of the 232 elected seats in the National Assembly, and Benjamin Mkapa was elected as president.[67]

The presidents of Tanzania since Independence have been Julius Nyerere 1962–1985, Ali Hassan Mwinyi 1985–1995, Benjamin Mkapa 1995–2005, Jakaya Kikwete 2005–2015, John Magufuli 2015–2021, and Samia Hassan Suluhu since 2021.[68] After the long tenure of president Nyerere, the Constitution has a term limit: a president can serve a maximum of two terms. Each term is five years.[69] Every president has represented the ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM).[70] President Magufuli won a landslide victory and re-election in October 2020. According to the opposition, the election was full of fraud and irregularities.[71]

On 17 March 2021, President John Magufuli died in office.[72] Magufuli's vice president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, became Tanzania's first female president.[73]

Geography

At 947,403 square kilometres (365,794 sq mi),[5] Tanzania is the 13th largest country in Africa and the 31st largest in the world, ranked between the larger Egypt and smaller Nigeria.[74] It borders Kenya and Uganda to the north; Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west; and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. Tanzania is located on the eastern coast of Africa and has an Indian Ocean coastline approximately 1,424 kilometres (885 mi) long.[75] It also incorporates several offshore islands, including Unguja (Zanzibar), Pemba, and Mafia.[76]: page 1245 The country is the site of Africa's highest and lowest points: Mount Kilimanjaro, at 5,895 metres (19,341 ft) above sea level, and the floor of Lake Tanganyika, at 1,471 metres (4,826 ft) below sea level, respectively.[76]: page 1245

Tanzania is mountainous and densely forested in the northeast, where Mount Kilimanjaro is located. Three of Africa's Great Lakes are partly within Tanzania. To the north and west lie Lake Victoria, Africa's largest lake, and Lake Tanganyika, the continent's deepest lake, known for its unique species of fish. To the southwest lies Lake Nyasa. Central Tanzania is a large plateau, with plains and arable land. The eastern shore is hot and humid, with the Zanzibar Archipelago just offshore.

Kalambo Falls in the southwestern region of Rukwa is the second highest uninterrupted waterfall in Africa, and is located near the southeastern shore of Lake Tanganyika on the border with Zambia.[27] The Menai Bay Conservation Area is Zanzibar's largest marine protected area.

Climate

Climate varies greatly within Tanzania. In the highlands, temperatures range between 10 and 20 °C (50 and 68 °F) during cold and hot seasons respectively. The rest of the country has temperatures rarely falling lower than 20 °C (68 °F). The hottest period extends between November and February (25–31 °C or 77.0–87.8 °F) while the coldest period occurs between May and August (15–20 °C or 59–68 °F). Annual temperature is 20 °C (68.0 °F). The climate is cool in high mountainous regions.

Tanzania has two major rainfall periods: one is uni-modal (October–April) and the other is bi-modal (October–December and March–May).[77] The former is experienced in southern, central, and western parts of the country, and the latter is found in the north from Lake Victoria extending east to the coast.[77] The bi-modal rainfall is caused by the seasonal migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone.[77]

Climate change in Tanzania is resulting in rising temperatures with a higher likelihood of intense rainfall events (resulting in flooding) and of dry spells (resulting in droughts).[78][79] Climate change is already impacting the sectors in Tanzania of agriculture, water resources, health and energy. Sea level rise and changes in the quality of water are expected to impact fisheries and aquaculture.[80]

Tanzania produced a National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs) in 2007 as mandated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In 2012, Tanzania produced a National Climate Change Strategy in response to the growing concern of the negative impacts of climate change and climate variability on the country's social, economic and physical environment.[81]

Wildlife and conservation

Tanzania contains around 20% of the species of Africa's enormous warm-blooded animal populace, found over its 21 National parks, reserves, 1 conservation area, and 3 marine parks. Spread over a zone of in excess of 42,000 square kilometres (16,000 sq. mi) and shaping around 38% of the nation's area.[82] Tanzania has 21 national parks,[83] plus a variety of game and forest reserves, including the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, however the local human population still has an impact on the environment. In western Tanzania, Gombe Stream National Park is the site of Jane Goodall's ongoing study of chimpanzee behaviour, which started in 1960.[84][85]

Tanzania is highly biodiverse and contains a wide variety of animal habitats.[86] On Tanzania's Serengeti plain, white-bearded wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus mearnsi), other bovids and zebra[87] participate in a large-scale annual migration. Tanzania is home to about 130 amphibian and over 275 reptile species, many of them strictly endemic and included in the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red Lists of countries.[88] Tanzania has the largest lion population in the world.[89]

Tanzania had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.13/10, ranking it 54th globally out of 172 countries.[90]

Politics

Government

Tanzania is a one-party dominant state with the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party in power. From its formation until 1992, it was the only legally permitted party in the country. This changed on 1 July 1992, when the constitution was amended.[91]: § 3 It has held power since independence in 1961, and is the longest-serving ruling party in Africa.[70]

John Magufuli won the October 2015 presidential election and secured a two-thirds majority in parliament.[92][93] The main opposition party in Tanzania since multiparty politics in 1992 is called Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (Chadema) (Swahili for "Party for Democracy and Progress"). The leader of Chadema party is Freeman Mbowe.[94]

In Zanzibar, the country's semi-autonomous state, The Alliance for Change and Transparency-Wazalendo (ACT-Wazalendo) is considered the main opposition political party. The constitution of Zanzibar requires the party that comes in second in the polls to join a coalition with the winning party. ACT-Wazalendo joined a coalition government with the islands' ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi in December 2020 after Zanzibar disputed elections.[95]

In November 2020, Magufuli once again was declared the winner for his second term as president. Election fraud was suspected. The national electoral commission announced that Magufuli received 84%, or about 12.5 million votes and the top opposition candidate, Tundu Lissu received 13%, about 1.9 million votes.[96]

In March 2021, it was announced that Magufuli had died whilst serving in office, meaning that his vice president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, became the country's president.[73]

Executive

The president of Tanzania and the members of the National Assembly are elected concurrently by direct popular vote for five-year terms.[91]: § 42(2) The vice-president is elected for a five-year term at the same time as the president and on the same ticket.[91]: §§ 47(2), 50(1) Neither the president nor the vice-president may be a member of the National Assembly.[91]: § 66(2) The president appoints a prime minister from among the members of the National Assembly, subject to confirmation by the assembly, to serve as the government's leader in the assembly.[91]: §§ 51(1)-(2), 52(2) The president selects her cabinet from assembly members.[91]: § 55 Law enforcement in Tanzania is under the executive branch of government and is administered by the Tanzania Police Force.[97]

Legislature

All legislative power relating to mainland Tanzania and union matters is vested in the National Assembly,[91]: § 64(1) which is unicameral and has 393 members.[98] These include members elected to represent constituencies, the attorney general, five members elected by the Zanzibar house of representatives from among its own members, the special women's seats that constitute at least 30% of the seats that any party has in the assembly, the speaker of the assembly (if not otherwise a member of the assembly), and the persons (not more than ten) appointed by the president.[91]: § 66(1) The Tanzania Electoral Commission demarcates the mainland into constituencies in the number determined by the commission with the consent of the president.[91]: § 75

Judiciary

Tanzania's legal system is based on English common law.[99]

Tanzania has a four-level judiciary.[99] The lowest-level courts on the Tanzanian mainland are the Primary Courts.[99] In Zanzibar, the lowest-level courts are the Kadhi's Courts for Islamic family matters and the Primary Courts for all other cases.[99] On the mainland, appeal is to either the District Courts or the Resident Magistrates Courts.[99] In Zanzibar, appeal is to the Kadhi's Appeal Courts for Islamic family matters and the Magistrates Courts for all other cases.[99] From there, appeal is to the High Court of Mainland Tanzania or Zanzibar.[99] No appeal regarding Islamic family matters can be made from the High Court of Zanzibar.[99][100]: § 99(1) Otherwise, the final appeal is to the Court of Appeal of Tanzania.[99]

The High Court of mainland Tanzania has three divisions – commercial, labour, and land[99] – and 15 geographic zones.[101] The High Court of Zanzibar has an industrial division, which hears only labour disputes.[102]

Mainland and union judges are appointed by the Chief Justice of Tanzania,[103] except for those of the Court of Appeal and the High Court, who are appointed by the president of Tanzania.[91]: §§ 109(1), 118(2)–(3)

Tanzania is a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[104]

Law enforcement

Public safety and border control is the responsibility of the Tanzania Police Force. Oversight of the force is shared by the Principal Secretary of the Ministry of Police and the Inspector-General of Police.[105]

Zanzibar

The legislative authority in Zanzibar over all non-union matters is vested in the House of Representatives (per the Tanzania constitution)[91]: § 106(3) or the Legislative Council (per the Zanzibar constitution).

The Legislative Council has two parts: the president of Zanzibar and the House of Representatives.[91]: § 107(1)-(2) [100]: § 63(1) The president is Zanzibar's head of government and the chairman of the Revolutionary Council, in which the executive authority of Zanzibar is invested.[100]: §§ 5A(2), 26(1) Zanzibar has two vice-presidents, with the first being from the main opposition party in the house.[106][107] The second is from the party in power and is the leader of government business in the House.[107]

The president and the members of the House of Representatives have five-year terms and can be elected for a second term.[100]: § 28(2)

The president selects ministers from members of the House of Representatives,[100]: § 42(2) with the ministers allocated according to the number of House seats won by political parties.[106] The Revolutionary Council consists of the president, both vice-presidents, all ministers, the attorney general of Zanzibar, and other house members deemed fit by the president.[106]

The House of Representatives is composed of elected members, ten members appointed by the president, all the regional commissioners of Zanzibar, the attorney general, and appointed female members whose number must be equal to 30 per cent of the elected members.[100]: §§ 55(3), 64, 67(1) The House determines the number of its elected members[100]: § 120(2) with the Zanzibar Electoral Commission determining the boundaries of each election constituency.[100]: § 120(1) In 2013, the House had 81 members: fifty elected members, five regional commissioners, the attorney general, ten members appointed by the president, and fifteen appointed female members.[98]

Leadership in World governance initiatives

Tanzania has been one of the signatories of the agreement to convene a convention for drafting a world constitution.[108][109] As a result, in 1968, for the first time in human history, a World Constituent Assembly convened to draft and adopt the Constitution for the Federation of Earth.[110] Julius Nyerere, then president of Tanzania signed the agreement to convene a World Constituent Assembly.[111]

Administrative subdivisions

In 1972, local government on the mainland was abolished and replaced with direct rule from the central government. Local government, however, was reintroduced in the beginning of the 1980s, when the rural councils and rural authorities were re-established. Local government elections took place in 1983, and functioning councils started in 1984. In 1999, a Local Government Reform Programme was enacted by the National Assembly, setting "a comprehensive and ambitious agenda ... [covering] four areas: political decentralization, financial decentralization, administrative decentralization and changed central-local relations, with the mainland government having overriding powers within the framework of the Constitution."[112]

Tanzania is divided into thirty-one regions (mikoa),[113][114] twenty-six on the mainland and five in Zanzibar (three on Unguja, two on Pemba).[115] The thirty-one regions are divided into 195 districts (wilaya), also known as local government authorities. Of those districts, 45 are urban units, which are further classified as three city councils (Arusha, Mbeya, and Mwanza), twenty municipal councils, and twenty-two town councils.[116]

The urban units have an autonomous city, municipal, or town council and are subdivided into wards and sub-wards (mitaa). The non-urban units have an autonomous district council but are subdivided into village councils or township authorities (first level) and then into hamlets (vitongoji).[112]

The city of Dar es Salaam is unique because it has a city council whose area of jurisdiction overlaps three municipal councils. The mayor of the city council is elected by that council. The twenty-member city council is composed of eleven persons elected by the municipal councils, seven members of the National Assembly, and "Nominated members of parliament under 'Special Seats' for women". Each municipal council also has a mayor. "The City Council performs a coordinating role and attends to issues cutting across the three municipalities", including security and emergency services.[117][118] The city of Mwanza has a city council whose areal jurisdiction overlaps two municipal councils.

Foreign policies and partnerships

Foreign policies of Tanzania are in process of review to replace the current New Foreign Policy of 2001, which was the first official foreign policy of Tanzania.[119][120] Before 2001, Tanzanian foreign policy was dictated by the various presidential declarations of Mwalimu Nyerere specifically Circular No. 2 of 1964,[121] Arusha Declaration,[122] and Policy of Foreign Affairs of 1967.[123] These declarations had focused foreign policy primarily on independence and sovereignty, human rights, and African unity.[124][125] The current New Foreign Policy of 2001 was established to better address the end of colonialism and the cold war, globalization, market economics and liberalization, and the multi-party state of Tanzania. Its primary focus is economic diplomacy and development.[126]

New Foreign Policy of 2001, which is still used today, has a foundation of 7 principles; sovereignty, liberalism, good neighborliness, African unity, non-alignment, economic diplomacy, and global cooperation for economic development and peace.[127] The primary objectives are outlined as the protection and promotion of cultural and economic interests, establishment of relations with other nations driven by economic interest, economic self-sufficiency, internal and global peace, and regional political and economic integration.[126][127]

A review of current foreign policy is being undertaken by the sixth phase government to replace the current New Foreign Policy of 2001.[119] Foreign Affairs Minister Liberata Mulamula has stated the new policies will maintain the priority of and non-alignment of the 2001 policy while making additional top priorities the climate change and refocusing economic diplomacy with a greater focus on value-added exports and the digital economy.[120]

International partnerships

Tanzania is a member of many international organizations such as the United Nations (UN), African Union (AU), East African Community (EAC), and Southern African Development Community (SADC) among many others.[128] Additionally, due to the strength of Tanzania's non-alignment, unity and internal peace since independence, Tanzania frequently acts as a mediator and location of treaties and agreements between other nations, such as the Arusha Agreement with Europe, as well as the Arusha Accords with Rwanda (1993) and Burundi (2000).[129][130]

The United Nations has a large current and historical presence in Tanzania and acts as an important partner in itself, and associated IGOs and NGOs, in many functions in the country, as well as functions based in Tanzania and implemented throughout the Great Lakes and Africa as a whole.[131] Of the many functions, the UN and Tanzania partner or the UN works with outside countries, most notably human rights and justice courts and reporting, education, development, climate change, health, and wildlife conservation.[132] While the UN primary offices are in Oysterbay, Dar es Salaam, many other offices, courts, and NGOs are based in Arusha, TZ. The most well-known example is the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda genocide.[133]

The African Union consists of 55 nations in Africa.[134] Tanzania is a founding member of the AU in 2001, and its predecessor the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) by the predecessors of Tanzania, Tanganyika and Zanzibar, in 1963. The Judicial Branch of the AU and its courts are located in Tanzania.[135] Originally the Court of Justice of the African Union, it has been combined with the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights to form the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR) which is located in Arusha.[135] Tanzania ratified and joined the AU-brokered African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) on 17 January 2022, the largest free trade area in the world.[136]

The East African Community consisting of Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is headquartered in Arusha.[137][138] Tanzania, along with Kenya and Uganda, is a founding member of the EAC in 2000.[139] Following the German defeat in World War I Tanzania joined the London-based East African Currency Board (EACB) that was a customs union and provider of currency for Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya from 1919 to 1948, the East Africa High Commission (EAHC) from 1948 to 1961, and East African Common Services Organization (EACSO) from 1961 to 1966. In 1966 all three countries formed the first East African Community which lasted until 1976, then the East African Co-operation from 1993 to 2000, before becoming reestablished as the East African Community in 2000.[139][140]

The EAC has had a customs union since 2005, with a free trade zone between member states and unified tariffs and trade agreements with non-member states and multinational organizations.[137] The customs union also established a unified organization and sets of rules, such as rules of origin, for all trade within, into, and passing through member states. In 2010 a common market was established within the EAC for the free movement of labor, goods, people, capital, and services, as well as established rights of establishment.[137] The East African Monetary Union (EAMU) is proposed to be established in 2024 that will create a single common currency by the East African Central Bank.[141] From the original reestablishment of the EAC, as laid out in Article 5(2) of the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community, the final goal for the EAC is always the political federation of all member states. In 2017 all member states adopted the confederation of EAC as a transitional precursor to the final federation.[137][140]

The Southern African Development Community consists of 16 nations, including all countries of southern Africa plus Tanzania and the DRC from the Great Lakes.[142] Tanzania is a founding member of SADC in 1994, as well as its predecessor the Frontline States (FLS), from 1960 to 1994. While FLS aimed to end apartheid, its successor SADC has the aims of furthering peace and security along with the economic and political integration of member states.[142]

Military

The Tanzania People's Defence Force (TPDF) (Kiswahili: Jeshi la Wananchi wa Tanzania (JWTZ)) is the armed forces of Tanzania, operating as a people's force under civilian control. It is composed of five branches or commands: Land Force (army), Air Force, Naval Command, National Service, Headquarter (MMJ).[143] Tanzanian citizens are able to volunteer for military service from 15 years of age, and 18 years of age for compulsory National military service upon graduation from advanced secondary school. Conscript service obligation was 2 years as of 2004.[needs update]

Tanzania is the 65th most peaceful country in the world, according to the 2024 Global Peace Index.[144]

Human rights

Throughout Tanzania, same sex acts are illegal and carry a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.[145] According to a 2007 Pew Research Centre survey, 95 percent of Tanzanians believed that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.[146]

People with albinism living in Tanzania are often attacked, killed or mutilated because of superstitions related to the black-magical practice known as muti that say body parts of albinos have magical properties.[147] Tanzania has the highest occurrence of this human rights violation among 27 African countries where muti is known to be practised.[148]

In December 2019, Amnesty International reported that the Tanzanian government annulled the right of NGOs as well as individuals to directly file any case against it at the Arusha-based African Court for Human and Peoples' Rights.[149]

Economy and infrastructure

As of 2021[update], according to the IMF, Tanzania's gross domestic product (GDP) was an estimated $71 billion (nominal), or $218.5 billion on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis. GDP per capita (PPP) was $3,574.[150]

From 2009 through to 2013, Tanzania's per capita GDP (based on constant local currency) grew an average of 3.5% per year, higher than any other member of the East African Community (EAC) and exceeded by only nine countries in Sub-Saharan Africa: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Lesotho, Liberia, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.[151]

Tanzania's largest trading partners in 2017 for its US$5.3 billion in exports were India, Vietnam, South Africa, Switzerland, and China.[152] Its imports totalled US$8.17 billion, with India, Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, China, and the United Arab Emirates being the biggest partners.[152]

Tanzania weathered the Great Recession, which began in late 2008 or early 2009, relatively well. Strong gold prices, bolstering the country's mining industry, and Tanzania's poor integration into global markets helped to insulate the country from the downturn.[76]: page 1250 Since the recession ended, the Tanzanian economy has expanded rapidly thanks to strong tourism, telecommunications, and banking sectors.[76]: page 1250

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), however, recent growth in the national economy has benefited only the "very few", leaving out the majority of the population.[153] As of the latest survey in 2015/2016, 57.1 percent of the population is considered to be affected by multidimensional poverty.[154] Tanzania's 2013 Global Hunger Index was worse than any other country in the EAC except Burundi.[155]: page 15 The proportion of persons who were undernourished in 2010–12 was also worse than any other EAC country except Burundi.[155]: page 51

In 2020, the World Bank declared the rise of the Tanzanian economy from low income to lower middle income country, as its GNI per capita increased from US$1,020 in 2018 to US$1,080 in 2019.[156][157]

Tanzania's economy grew 4.6 percent in 2022, and 5.2 percent in 2023.[158]

Hunger and poverty

The Global Hunger Index previously ranked the situation as "alarming" with a score of 42 in the year 2000; since then the GHI has declined to 23.2.[159] Children in rural areas suffer substantially higher rates of malnutrition and chronic hunger, although urban-rural disparities have narrowed as regards both stunting and underweight.[160] Low rural sector productivity arises mainly from inadequate infrastructure investment; limited access to farm inputs, extension services and credit; limited technology as well as trade and marketing support; and heavy dependence on rain-fed agriculture and natural resources.[160]

Approximately 68 percent of Tanzania's 61.1 million citizens live below the poverty line of $1.25 a day. 32 percent of the population are malnourished.[159] The most prominent challenges Tanzania faces in poverty reduction are unsustainable harvesting of its natural resources, unchecked cultivation, climate change and water source encroachment, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).[161]

There are very few resources for Tanzanians in terms of credit services, infrastructure or availability to improved agricultural technologies, which further exacerbates hunger and poverty in the country according to the UNDP.[161] Tanzania ranks 159 out of 187 countries in poverty according to the United Nation's Human Development Index (2014).[161]

The 2019 World Bank report showed that in the last 10 years, poverty has reduced by 8 percentage points, from 34.4% in 2007 to 26.4% in 2018.[162] A further report showed a reduction to 25.7% in 2020.[163]

Agriculture

The Tanzanian economy is heavily based on agriculture, which in 2013 accounted for 24.5 per cent of gross domestic product,[56]: page 37 provides 85% of exports,[15] and accounted for half of the employed workforce.[56]: page 56 The agricultural sector grew 4.3 percent in 2012, less than half of the Millennium Development Goal target of 10.8%.[164] 16.4 per cent of the land is arable,[165] with 2.4 percent of the land planted with permanent crops.[166] Tanzania's economy relies on farming, but climate change has impacted their farming.

Maize was the largest food crop on the Tanzania mainland in 2013 (5.17 million tonnes), followed by cassava (1.94 million tonnes), sweet potatoes (1.88 million tonnes), beans (1.64 million tonnes), bananas (1.31 million tonnes), rice (1.31 million tonnes), and millet (1.04 million tonnes).[56]: page 58 Sugar was the largest cash crop on the mainland in 2013 (296,679 tonnes), followed by cotton (241,198 tonnes), cashew nuts (126,000 tonnes), tobacco (86,877 tonnes), coffee (48,000 tonnes), sisal (37,368 tonnes), and tea (32,422 tonnes).[56]: page 58 Beef was the largest meat product on the mainland in 2013 (299,581 tonnes), followed by lamb/mutton (115,652 tonnes), chicken (87,408 tonnes), and pork (50,814 tonnes).[56]: page 60

According to the 2002 National Irrigation Master Plan, 29.4 million hectares in Tanzania are suitable for irrigation farming; however, only 310,745 hectares were actually being irrigated in June 2011.[167]

Industry, energy and construction

Industry and construction is a major and growing component of the Tanzanian economy, contributing 22.2 per cent of GDP in 2013.[56]: page 37 This component includes mining and quarrying, manufacturing, electricity and natural gas, water supply, and construction.[56]: page 37 Mining contributed 3.3 per cent of GDP in 2013.[56]: page 33 The vast majority of the country's mineral export revenue comes from gold, accounting for 89 per cent of the value of those exports in 2013.[56]: page 71 Tanzania's gold production is 46 metric tonnes in 2015.[168] It also exports sizeable quantities of gemstones, including diamonds and tanzanite.[76]: page 1251 All of Tanzania's coal production, which totalled 106,000 short tons in 2012, is used domestically.[169]

Only 15 percent of Tanzanians had access to electric power in 2011, rising to 35.2 per cent in 2018.[170] The government-owned Tanzania Electric Supply Company Limited (TANESCO) dominates the electric supply industry in Tanzania.[171][e] The country generated 6.013 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity in 2013, a 4.2 per cent increase over the 5.771 billion kWh generated in 2012.[173]: page 4 Generation increased by 63 percent between 2005 and 2012;[174][175] Almost 18 percent of the electricity generated in 2012 was lost because of theft and transmission and distribution problems.[174] The electrical supply varies, particularly when droughts disrupt hydropower electric generation; rolling blackouts are implemented as necessary.[76]: page 1251 The unreliability of the electrical supply has hindered the development of Tanzanian industry.[76]: page 1251 In 2013, 49.7 percent of Tanzania's electricity generation came from natural gas, 28.9 percent from hydroelectric sources, 20.4 percent from thermal sources, and 1.0 percent from outside the country.[173]: page 5 The government has built a 532 kilometres (331 mi) gas pipeline from Mnazi Bay to Dar es Salaam.[176] This pipeline was expected to allow the country to double its electricity generation capacity to 3,000 megawatts by 2016.[177] The government's goal is to increase capacity to at least 10,000 megawatts by 2025.[178]

According to PFC Energy, 25 to 30 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas resources have been discovered in Tanzania since 2010,[169] bringing the total reserves to over 43 trillion cubic feet by the end of 2013.[179] The value of natural gas actually produced in 2013 was US$52.2 million, a 42.7 percent increase over 2012.[56]: page 73

Commercial production of gas from the Songo Songo Island field in the Indian Ocean commenced in 2004, thirty years after it was discovered there.[180][181] Over 35 billion cubic feet of gas was produced from this field in 2013,[56]: page 72 with proven, probable, and possible reserves totalling 1.1 trillion cubic feet.[181] The gas is transported by pipeline to Dar es Salaam.[180] As of 27 August 2014, TANESCO owed the operator of this field, Orca Exploration Group Inc.[182]

A newer natural gas field in Mnazi Bay in 2013 produced about one-seventh of the amount produced near Songo Songo Island[56]: page 73 but has proven, probable, and possible reserves of 2.2 trillion cubic feet.[181] Virtually all of that gas is being used for electricity generation in Mtwara.[180]

The Ruvuma and Kiliwani areas of Tanzania have been explored mostly by the discovery company that holds a 75 percent interest, Aminex, and has shown to hold in excess of 3.5 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. A pipeline connecting offshore natural gas fields to Tanzania's commercial capital Dar es Salaam was completed at the end of April 2015.[183]

Tourism

Travel and tourism contributed 17.5 per cent of Tanzania's gross domestic product in 2016[184] and employed 11.0 per cent of the country's labour force (1,189,300 jobs) in 2013.[185] Overall receipts rose from US$1.74 billion in 2004 to US$4.48 billion in 2013,[185] and receipts from international tourists rose from US$1.255 billion in 2010 to US$2 billion in 2016.[184][186] In 2016, 1,284,279 tourists arrived at Tanzania's borders compared to 590,000 in 2005.[152] The vast majority of tourists visit Zanzibar or a "northern circuit" of Serengeti National Park, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tarangire National Park, Lake Manyara National Park, and Mount Kilimanjaro.[76]: page 1252 In 2013, the most visited national park was Serengeti (452,485 tourists), followed by Manyara (187,773) and Tarangire (165,949).[56]: page xx

Banking

The Bank of Tanzania is the central bank of Tanzania and is primarily responsible for maintaining price stability, with a subsidiary responsibility for issuing the banknotes and coins of the Tanzanian shilling.[187] At the end of 2013, the total assets of the Tanzanian banking industry were TSh 19.5 trillion, a 15 per cent increase over 2012.[188]

Transport

Most transport in Tanzania is by road, with road transport constituting over 75 per cent of the country's freight traffic and 80 percent of its passenger traffic.[76]: page 1252 The Cairo-Cape Town Highway passes through Tanzania. The 181,191 kilometres (112,587 mi) road system is in generally poor condition.[76]: page 1252 Tanzania has two railway companies: TAZARA, which provides service between Dar es Salaam and Kapiri Mposhi (in a copper-mining district in Zambia), and Tanzania Railways Limited, which connects Dar es Salaam with central and northern Tanzania.[76]: page 1252 Rail travel in Tanzania often entails slow journeys with frequent cancellations or delays, and the railways have a deficient safety record.[76]: page 1252

In Dar es Salaam, there is a huge project of rapid buses, Dar Rapid Transit (DART) which connects suburbs of Dar es Salaam city. The development of the DART system consists of six phases and is funded by the African Development Bank, the World Bank and the Government of Tanzania. The first phase began in April 2012, and it was completed in December 2015 and launched operations in May 2016.[189]

Tanzania has four international airports, along with over 120 small airports or landing strips. Airport infrastructure tends to be in poor condition.[76]: page 1253 Airlines in Tanzania include Air Tanzania, Precision Air, Fastjet, Coastal Aviation, and ZanAir.[76]: page 1253

Communications

In 2013, the communications sector was the fastest growing in Tanzania, expanding 22.8 per cent; however, the sector accounted for only 2.4 per cent of gross domestic product that year.[173]: page 2

As of 2011, Tanzania had 56 mobile telephone subscribers per 100 inhabitants, a rate slightly above the sub-Saharan average.[76]: page 1253 Very few Tanzanians have fixed-line telephones.[76]: page 1253 Approximately 12 per cent of Tanzanians used the internet as of 2011[update], though this number is growing rapidly.[76]: page 1253 The country has a fibre-optic cable network that replaced unreliable satellite service, but internet bandwidth remains very low.[76]: page 1253

Economic statistics controversy

Two articles in the Economist in July 2020 raised doubts about official claims of economic growth: "If Tanzania's economy grew by almost 7% in the fiscal year to the end of June 2019, why did tax revenue fall by 1%? And why has bank lending to companies slumped? Private data are bad, too. In 2019 sales at the biggest brewer fell by 5%. Sales of cement by the two biggest producers were almost flat. None of these things is likely if growth is storming ahead. The discrepancies are so large that it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the government is lying."[190][191]

Tim Staermose, a proponent of African investment, took issue with these data: "Some of these statements by The Economist, based on the evidence I have gathered from primary sources – namely, the statutory financial reports that listed companies in Tanzania are legally obligated to release – are simply not true. Bank lending to companies as far as I can see has not, 'slumped.' The two biggest banks in Tanzania, which between them account for approximately 40% of the banking sector, both reported strong loan growth in 2019. ... As for cement sales being 'almost flat,' again, this is total nonsense. ... In 2019 Twiga sold 6% more cement by volume than it did in 2018. In the first six months of 2020, Twiga already sold 8% more cement than it had done by the same stage in 2019. Again, these numbers are very consistent with an economy that's reported to be growing at around 7% per annum. ... [On] the 5% fall in beer sales in 2019 ... the published 2019 annual report by Tanzania Breweries Limited (TBL) will tell you there were one-off circumstances that largely drove the decline ... [which] resulted in sales falling. But TBL's profits actually rose in 2019."[192]

Food and nutrition

Poor nutrition remains a persistent problem within Tanzania and varies hugely throughout the country's regions. USAID reports that 16% of children are underweight and 34% experience stunted growth as a result of malnutrition.[193] 10 regions house 58% of children suffering from stunted growth while 50% of acutely malnourished children can be found in 5 regions.[194] Over a 5-year period, the Mara district of Tanzania saw a 15% reduction in stunting in children under 5 years old, falling from 46% to 31% in 2005 and 2010 respectively. Dodoma, on the other hand, saw a 7% increase in the prevalence of stunting in this age group, rising from 50% in 2005 to 57% in 2010.[195] Overall availability of food does not necessarily contribute to overall stunting figures. Iringa, Mbeya and Rukwa regions, where overall availability of food is considered acceptable, still experience stunting incidents in excess of 50%. In some areas where food shortages are common, such as in the Tabora and Singida regions, stunting instances remain comparatively less than those seen in Iringa, Mbeya and Rukwa.[195] The Tanzania Food and Nutrition Centre attributes these discrepancies to variance in maternal malnutrition, poor infant feeding practices, hygiene practices and poor healthcare services.[195] Periods of drought can have significant impacts on the production of crops in Tanzania. Drought in East Africa has resulted in massive increases in the prices of food staples such as maize and sorghum, crops crucial to the nutrition of the majority of Tanzania's population. From 2015 to 2017 the price of maize when bought wholesale more than tripled, from TSh 400/= per kilogramme to 1,253/= per kilogramme.[196]

Tanzania remains heavily agricultural, with 80% of the total population engaging in subsistence farming.[196] Rural areas are subjected to increased food shortages in comparison to urbanised areas, with a survey carried out within the country in 2017 finding 84% of people in rural areas suffering food shortages over a 3-month period compared to 64% of residents in cities.[196] This disparity between rural and city nutrition can be attributed to various factors; increased nutritional needs due to manual labour, more limited access to food as a result of poor infrastructure, high-susceptibility to the damaging effects of nature and the "Agricultural Productivity Gap".[197] The Agricultural Productivity Gap postulates that "value added per worker" is often much lower within the agricultural sector than that found within non-agricultural sectors. Furthermore, allocation of labour within the agricultural sector is largely allocated ineffectively.[198]

Programmes targeting hunger

USAID programmes focusing on nutrition operate within the Morogoro, Dodoma, Iringa, Mbeya, Manyara, Songwe and Zanzibar regions of Tanzania. These "Feed the Future" programmes heavily invest in nutrition, infrastructure, policy, capacity of institutions and agriculture which is identified by the organisation as a key area of economic growth in the country.[193] A Tanzanian government led initiative "Kilimo Kwanza" or "Agriculture First" aims to encourage investment into agriculture within the private sector and hopes to improve agricultural processes and development within the country by seeking the knowledge of young people and the innovation that they can potentially provide.[199] During the 1990s, around 25% of Tanzania's population were provided access to iodised oil aimed to target iodine deficiency within expecting mothers, as result of studies showing the negative effects of in-utero iodine deficiency on cognitive development in children. Research showed that children of mothers with access to the supplement achieved on average greater than a third of a year more education than those who did not.[199]

Programmes led by the World Food Programme operate within Tanzania. The Supplementary Feeding Programme (SFP) aims to target acute malnutrition by supplying blended food fortified with vitamins to pregnant women and mothers to children under 5 on a monthly basis.[200] Pregnant women and mothers to children under 2 have access to the Mother and Child Health and Nutrition Programme's "Super Cereal" which is supplied with the intent of reducing stunting in children.[200] World Food Programme supplementation remains the main food source for Tanzania's refugees. Super Cereal, Vegetable Oil, Pulses and Salt are supplied as part of the Protracted Relief and Recovery Operation to meet the average person's minimum daily caloric requirement of 2,100 kcal.[200] UNICEF state that continued investment in nutrition within Tanzania is of the utmost importance: Estimates predict that Tanzania stands to lose $20 billion by 2025 if nutrition within the country remains at its current level, however improvements in nutrition could produce a gain of around $4.7 billion[194]

Save the Children, with the help of UNICEF and Irish Aid funding created the Partnership for Nutrition in Tanzania (PANITA), in 2011. PANITA aims to use civil society organisations to target nutrition within the country. Alongside this, various sectors associated with nutrition are targeted such as agriculture, water, sanitation, education, economic development and social progress. PANITA is responsible for ensuring significant attention is given to nutrition in development plans and budgets created on national and regional levels within Tanzania. Since its conception, PANITA has grown from 94 to 306 participating civil society organisations nationwide.[201] Agriculture within Tanzania is targeted by the Irish Aid led initiative Harnessing Agriculture for Nutrition Outcomes (HANO), which aims to merge nutrition initiatives with agriculture in the Lindi District of the country. The project aims to reduce stunting by 10% in children aged 0 to 23 months.[201]

Science and technology

Tanzania's first "National Science and Technology Policy" was adopted in 1996. The objective of the government's "Vision 2025" (1998) document was to "transform the economy into a strong, resilient and competitive one, buttressed by science and technology".

Under the umbrella of the One UN Initiative, UNESCO and Tanzanian government departments and agencies formulated a series of proposals in 2008 for revising the "National Science and Technology Policy". The total reform budget of US$10 million was financed from the One UN fund and other sources. UNESCO provided support for mainstreaming science, technology, and innovation into the new "National Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy" for the mainland and Zanzibar namely, Mkukuta II and Mkuza II, including in the field of tourism.[citation needed]

Tanzania's revised science policy was published in 2010. Entitled "National Research and Development Policy", it recognises the need to improve the process of prioritisation of research capacities, develop international co-operation in strategic areas of research and development, and improve planning for human resources. It also makes provisions for the establishment of a National Research Fund. This policy was, in turn, reviewed in 2012 and 2013.[202]

In 2010, Tanzania devoted 0.38 per cent of GDP to research and development. The global average in 2013 was 1.7 per cent of GDP. Tanzania had 69 researchers (in head counts) per million population in 2010. In 2014, Tanzania counted 15 publications per million inhabitants in internationally catalogued journals, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded). The average for sub-Saharan Africa was 20 publications per million inhabitants and the global average 176 publications per million inhabitants. Tanzania was ranked 120th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024, down from 97th in 2019.[203][204][205]

Demographics

| Year | Million |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 7.9 |

| 2000 | 35.1 |

| 2021 | 63.6 |

According to the 2012 census, the total population of Tanzania was 44,928,923.[208] The under-15 age group represented 44.1% of the population.[209]

The population distribution in Tanzania is significantly uneven. Most people live on the northern border or the coast, with much of the remainder of the country being sparsely populated.[76]: page 1252 Density varies from 12 per square kilometre (31/sq mi) in the Katavi Region to 3,133 per square kilometre (8,110/sq mi) in the Dar es Salaam Region.[208]: page 6

Approximately 70% of the population is rural, although this percentage has been declining since at least 1967.[210] Dar es Salaam (population 4,364,541)[211] is the largest city and commercial capital. The capital of the country and economic centre of Tanzania, Dodoma (population 410,956)[211] is located in central Tanzania, and hosts the National Assembly.

At the time of the foundation of the United Republic of Tanzania in 1964, the child mortality rate was 335 deaths per 1,000 live births. Since independence, the rate of child deaths has declined to 62 per 1000 births.[212]

Largest cities or towns in Tanzania

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||||||

Dar es Salaam  Mwanza |

1 | Dar es Salaam | Dar es Salaam | 4,364,541 |  Arusha  Dodoma | ||||

| 2 | Mwanza | Mwanza | 706,543 | ||||||

| 3 | Arusha | Arusha | 416,442 | ||||||

| 4 | Dodoma | Dodoma | 410,956 | ||||||

| 5 | Mbeya | Mbeya | 385,279 | ||||||

| 6 | Morogoro | Morogoro | 315,866 | ||||||

| 7 | Tanga | Tanga | 273,332 | ||||||

| 8 | Kahama | Shinyanga | 242,208 | ||||||

| 9 | Tabora | Tabora | 226,999 | ||||||

| 10 | Zanzibar City | Zanzibar West | 223,033 | ||||||

The population consists of about 125 ethnic groups.[213] The Sukuma, Nyamwezi, Chagga, and Haya peoples each have a population exceeding 1 million.[214]: page 4 Most Tanzanians are of native African descent. Tanzanian citizens of Indian descent constitute a significant demographic minority which is particularly prominent in business and entrepreneurship. There are also Tanzanians of Chinese descent.[215] Many Tanzanians identify as Shirazis. Some Tanzanians are of Arab descent.[213] The majority of Tanzanians, including the Sukuma and the Nyamwezi, are Bantu.[216]

Thousands of Arabs and Indians were massacred during the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964.[57] As of 1994, the Asian community numbered 50,000 on the mainland and 4,000 on Zanzibar. An estimated 70,000 Arabs and 10,000 Europeans lived in Tanzania.[217] As of 2015, the Indian community numbered 60,000.[218]

Some albinos in Tanzania have been the victims of violence in recent years.[219][220][221][222] Attacks are often to hack off the limbs of albinos in the perverse superstitious belief that possessing the bones of albinos will bring wealth. The country has banned witch doctors to try to prevent the practice, but it has continued and albinos remain targets.[223]

According to 2010 Tanzanian government statistics, the total fertility rate in Tanzania was 5.4 children born per woman, with 3.7 in urban mainland areas, 6.1 in rural mainland areas, and 5.1 in Zanzibar.[224]: page 55 For all women aged 45–49, 37.3 per cent had given birth to eight or more children, and for currently married women in that age group, 45.0 per cent had given birth to that many children.[224]: page 61

Religion

Official statistics on religion are unavailable because religious surveys were eliminated from government census reports after 1967.[225] Tanzania's religious field is dominated by Christianity, Islam and African traditional religions connected to ethnic customs. The word for religion in Swahili, dini, generally apply to the world religions of Christianity and Islam meaning that followers of traditional African religions are considered to be of "no religion". Religious belonging is often ambiguous, with some people adhering to multiple religious identities at the same time (for instance being Christian but also following African traditional rituals) something which suggests that religious boundaries are flexible and contextual.[226]

According to a 2014 estimate by the CIA World Factbook, 61.4% of the population was Christian, 35.2% was Muslim, 1.8% practised traditional African religions, 1.4% were unaffiliated with any religion, and 0.2% followed other religions. However, according to the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), 55.3% of the population is Christian, 31.5% is Muslim, 11.3% practices traditional faiths, while 1.9% of the population is non-religious or adheres to other faiths as of 2020.[227] The ARDA estimates that most Tanzanian Muslims are Sunni, with a small Shia minority, as of 2020.[227] Nearly the entire population of Zanzibar is Muslim.[15] Of Muslims, 16% are Ahmadiyya, 20% are non-denominational Muslims, 40% are Sunni, 20% are Shia, and 4% are Sufi.[228] Most Shias in Tanzania are from Asian/Indian descent.[229] Notable Shias of Indian/Khoja heritage in Tanzania are Mohammed Dewji or Amir H. Jamal.

Within the Christian community the Catholic Church is the largest group (51% all Christians).[230] Among the Protestants, the large number of Lutherans and Moravians points to the German missionary past of the country, while the number of Anglicans point to the British missionary history of Tanganyika. A growing number have adopted Pentecostalism, and Adventists likewise have an increasing presence because of external missionary activities from Scandinavia and the United States, especially during the first part of the 20th century.[231] All of them have had some influence in varying degrees from the Walokole movement (East African Revival), which has also been fertile ground for the spread of charismatic and Pentecostal groups.[232] The country also has around 20,000 Jehovah's Witnesses.[233]

There are also active communities of other religious groups, primarily on the mainland, such as Buddhists, Hindus, and Bahá'ís.[234]

Languages

More than 100 languages are spoken in Tanzania, making it the most linguistically diverse country in East Africa.[24] Among the languages spoken are four of Africa's language families: Bantu, Cushitic, Nilotic, and Khoisan.[24] There are no de jure official languages in Tanzania.[25]

Swahili is used in parliamentary debate, in the lower courts, and as a medium of instruction in primary school. English is used in foreign trade, in diplomacy, in higher courts, and as a medium of instruction in secondary and higher education.[24] The Tanzanian government, however, has plans to discontinue English as a language of instruction.[26] In connection with his Ujamaa social policies, President Nyerere encouraged the use of Swahili to help unify the country's many ethnic groups.[235] Approximately 10 per cent of Tanzanians speak Swahili as a first language, and up to 90 per cent speak it as a second language.[24] Many educated Tanzanians are trilingual, also speaking English.[236][237][238] The widespread use and promotion of Swahili is contributing to the decline of smaller languages in the country.[24][239] Young children increasingly speak Swahili as a first language, particularly in urban areas.[240] Ethnic community languages (ECL) other than Kiswahili are not allowed as a language of instruction. Nor are they taught as a subject, though they might be used unofficially in some cases in initial education. Television and radio programmes in an ECL are prohibited, and it is nearly impossible to get permission to publish a newspaper in an ECL. There is no department of local or regional African Languages and Literatures at the University of Dar es Salaam.[241]

The Sandawe people speak a language that may be related to the Khoe languages of Botswana and Namibia, while the language of the Hadzabe people, although it has similar click consonants, is arguably a language isolate.[242] The language of the Iraqw people is Cushitic.[243]

Education and Libraries

In 2015, the literacy rate in Tanzania was 77.9% for people aged 15 and over (83.2% males, 73.1% females).[244] Education is compulsory until children reach age 15.[245] In 2020, 97% completed primary (98.4% females and 95.5% males), 28.3% completed secondary (30% females and 27% males), and 8% completed tertiary education (7% females and 8.5% males).[246]

The Tanzania Library Services Board operates twenty-one regional, eighteen district, and one divisional library.[247][248]

Healthcare

As of 2012[update], life expectancy at birth was 61 years.[249] The under-five mortality rate in 2012 was 54 per 1,000 live births.[249] The maternal mortality rate in 2013 was estimated at 410 per 100,000 live births.[249] Prematurity and malaria were tied in 2010 as the leading cause of death in children under five years old.[250] The other leading causes of death for these children were, in decreasing order, malaria, diarrhoea, HIV, and measles.[250]

Malaria in Tanzania causes death and disease and has a "huge economic impact".[251]: page 13 There were approximately 11.5 million cases of clinical malaria in 2008.[251]: page 12 In 2007–08, malaria prevalence among children aged 6 months to five years was highest in the Kagera Region (41.1 per cent) on the western shore of Lake Victoria and lowest in the Arusha Region (0.1 per cent).[251]: page 12

According to the 2010 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010, 15 per cent of Tanzanian women had undergone female genital mutilation (FGM)[224]: page 295 and 72 per cent of Tanzanian men had been circumcised.[224]: page 230 FGM is most common in the Manyara, Dodoma, Arusha, and Singida regions and nonexistent in Zanzibar.[224]: page 296 The prevalence of male circumcision was above 90 per cent in the eastern[223] (Dar es Salaam, Pwani, and Morogoro regions), northern (Kilimanjaro, Tanga, Arusha, and Manyara regions), and central areas (Dodoma and Singida regions) and below 50 per cent only in the southern highlands zone (Mbeya, Iringa, and Rukwa regions).[224]: pages 6, 230

2012 data showed that 53 per cent of the population used improved drinking water sources (defined as a source that "by nature of its construction and design, is likely to protect the source from outside contamination, in particular from faecal matter") and 12 per cent used improved sanitation facilities (defined as facilities that "likely hygienically separates human excreta from human contact" but not including facilities shared with other households or open to public use).[252]

Women

Women and men have equality before the law.[253] The government signed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 1985.[253] Nearly 3 out of ten women reported having experienced sexual violence before the age of 18. [253] The prevalence of female genital mutilation has decreased.[253] School girls are reinstated back to school after delivery.[253] The Police Force administration strives to separate the Gender Desks from normal police operations to enhance confidentiality of the processing of women victims of abuse.[253] Most of the abuses and violence against women and children occurs at the family level.[253] The Constitution of Tanzania requires that women constitute at least 30% of all elected members of National Assembly.[253] The gender differences in education and training have implications later in life of these women and girls.[253] Unemployment is higher for females than for males.[253] The right of a female employee to maternity leave is guaranteed in labour law.[253]

Culture

Media

Music

As in other countries, the music in Tanzania is constantly undergoing changes, and varies by location, people, settings and occasion. The five music genres in Tanzania, as defined by BASATA are, ngoma, dansi, kwaya, and taarab, with bongo flava being added in 2001.[254][255] Singeli has since the mid-2000s been an unofficial music of uswahilini, unplanned communities in Dar es Salaam, and is the newest mainstream genre since 2020.[256]

Ngoma (Bantu, meaning dance, drum and event)[257][258] is a traditional dance music that has been the most widespread music in Tanzania.[259][260] Dansi is urban jazz or band music.[259][261] Taarab is sung Kiswahili poetry accompanied by a band, typically string, in which audience is often, but not always, encouraged to dance and clap.[259] Kwaya was choir music originally limited to church during colonization, but is now a secular part of educational, social, and political events.[257][260]

Bongo flava is Tanzanian pop music originating in the early 2000s from muziki wa kizazi kipya, meaning "Music of the new generation", which originated in the late 1980s. Kizazi kipya's dominant influences were reggae, RnB, and hip hop, where as the later bongo flava's dominant influences are taarab and dansi.[262] Three recent influence on bongo flava are Afropop in the 2010s, as well as amapiano from South Africa and singeli from Tanzania, both since 2020.[263][264] Singeli is a ngoma music that originated in Manzese, an uswahilini in north-west Dar es Salaam. A MC performs over fast tempo taarab music, often at between 200 and 300 beats per minute (BPM) while females dance. Styles between MC gender typically differ significantly. Male MCs usually perform in fast-paced rap, while female MCs usually perform kwaya.[256]

From independence until 1993, all recording and distribution of music was strictly managed by BASATA, primarily through Radio Tanzania Dar es Salaam (RTD).[265] Only the four Tanzanian genres were permitted to be recorded or broadcast, which at the time was ngoma, taarab, kwaya and dansi. The Broadcasting Services Act of 1993 allowed private broadcast networks and recording studios.[266][267] In the few years prior to the 1993 Act hip hop had been getting somewhat established in Dar es Salaam, Arusha and Mwanza. It was transitioning from English performances of hip hop originating in uzunguni, rich areas like Oysterbay and Masaki with international schools, to Kiswahili performances of kizazi kipya, originating in uswahilini.[268] Following the opening of the radio waves, bongo flava spreading throughout the country, and the rest of the Great Lakes.[262]

National anthem

The Tanzanian national anthem is "Mungu Ibariki Africa" (God Bless Africa). It has kiswahili lyrics adapted for "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika" composed by South African composer Enoch Sontonga in 1897.[270] "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika" became a pan-African song adapted into the current national anthems for Tanzania, Zambia, and following the end of apartheid South Africa.[271] It was previously used in the national anthems for Zimbabwe and Namibia, but has since been replaced by original new anthems. Another patriotic song is Tanzania, Tanzania.

Literature

Tanzania's literary culture is primarily oral.[214]: page 68 Major oral literary forms include folktales, poems, riddles, proverbs, and songs.[214]: page 69 The greatest part of Tanzania's recorded oral literature is in Swahili, even though each of the country's languages has its own oral tradition.[214]: pages 68–69 The country's oral literature has been declining because of the breakdown of the multigenerational social structure, making transmission of oral literature more difficult, and because increasing modernisation has been accompanied by the devaluation of oral literature.[214]: page 69

Books in Tanzania are often expensive and hard to come by.[214]: page 75 [272]: page 16 Most Tanzanian literature is in Swahili or English.[214]: page 75 Major figures in Tanzanian written literature include Shaaban Robert (considered the father of Swahili literature), Aniceti Kitereza, Muhammed Saley Farsy, Faraji Katalambulla, Adam Shafi Adam, Muhammed Said Abdalla, Peter K. Palangyo, Said Ahmed Mohammed Khamis, Mohamed Suleiman Mohamed, Euphrase Kezilahabi, Gabriel Ruhumbika, Ebrahim Hussein, May Materru Balisidya, Fadhy Mtanga, Abdulrazak Gurnah, and Penina O. Mlama.[214]: pages 76–8

Painting and sculpture